Defender: The Last Word

This evening, I’ve checked an item off my to-do list that was over 30 years old: publish Defender book. Check. Done. Here it is:

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Getting Started

- Chapter 2: The Controls

- Chapter 3: Landers

- Chapter 4: Mutants

- Chapter 5: Swarmers

- Chapter 6: Bombers

- Chapter 7: Baiters

- Chapter 8: Catching Humanoids

- Chapter 9: Free Space

- Chapter 10: Strategy

- Chapter 11: Miscellaneous

- Chapter 12: Stargate

- Chapter 13: Attitude

- Acknowledgments

How this book came to be

Defender was a coin-op video game released by Williams Electronics in 1981. After a slow start due to its intimidating complexity, it became one of the most influential and popular video games of all time, generating more than $1 billion in revenue.

Pac-Man is the only other coin-op game to achieve that level of success, but Defender and Pac-Man were radically different games. Pac-Man started slowly, with intuitively obvious game play and an overall peaceful vibe that rewarded careful planning and memorization of repetitive patterns. Defender, by comparison, thrust the player into a relentless barrage of ever-escalating violent chaos, with controls so complicated that even experienced gamers sometimes found their first game over in seconds.

I fell instantly in love with Defender, and it truly changed the course of my life.

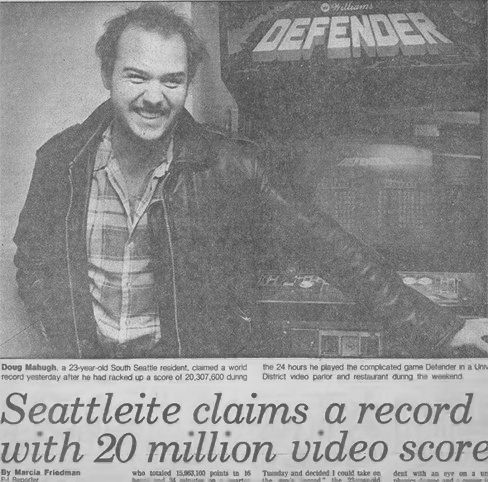

I learned to play Defender at the Spot (south Renton), on lunch breaks from my job as a Fortran programmer at Boeing’s Valley Office Park facility over on Lind Avenue. Well, is it a “lunch break” if you show up at noon and close the bar down, playing Defender the whole time? In any event, I played Defender a lot, and was lucky enough to find that I had a bit of aptitude for the game. I won every Defender contest I entered for a couple of years, collecting various prizes up to an Atari game console and $1000 cash.

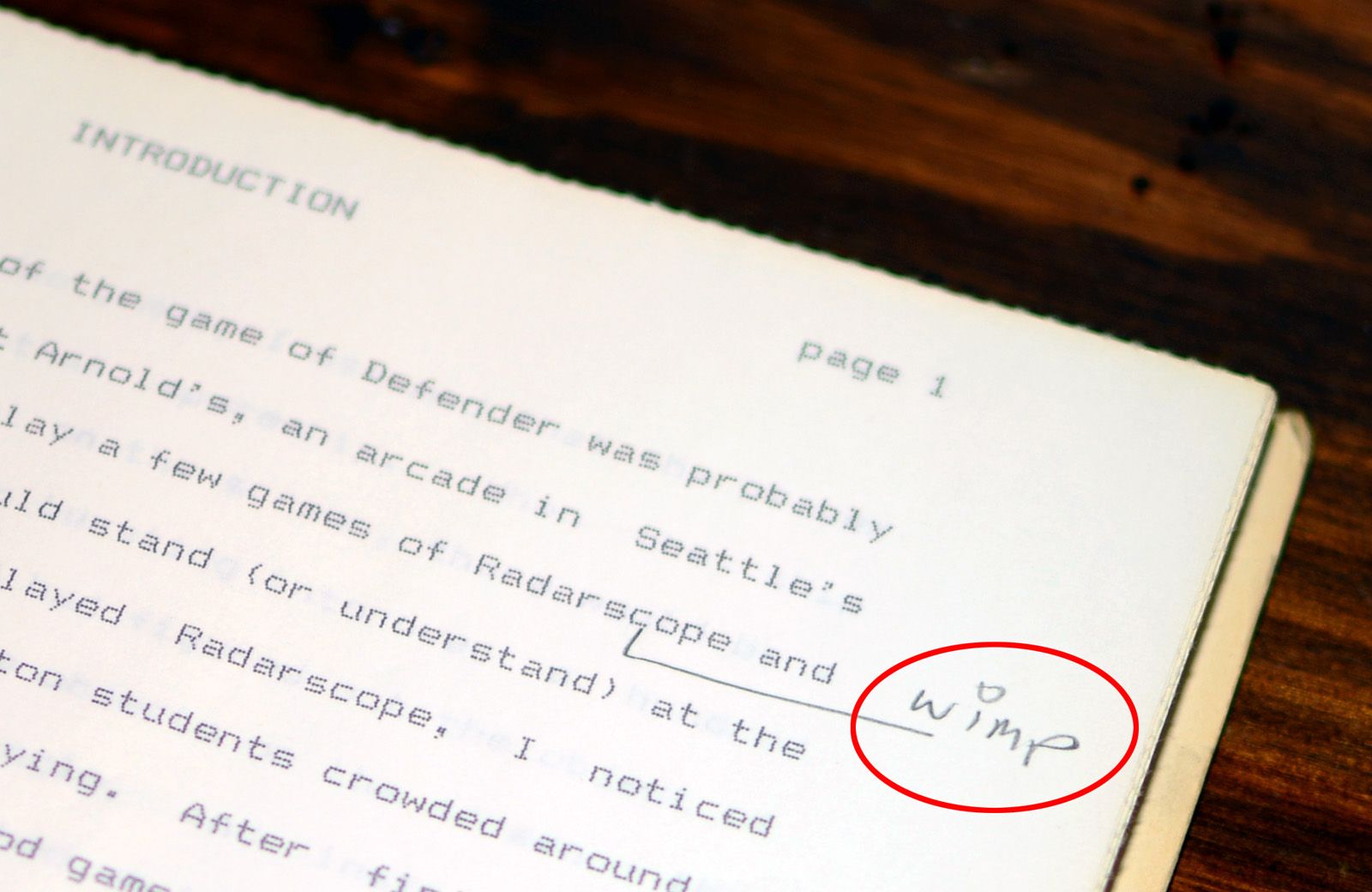

So I did the predictable thing: I quit my job at Boeing (hey, it was interfering with my video game playing!) and spent three months writing the ultimate guide to Defender. I wrote it in WordStar on a Heath H-89 CP/M computer that I had helped my Dad build, and I wrote GW-BASIC programs to generate dot-matrix graphics on an Epson MX-80 for crude artwork to illustrate some of the concepts. I tracked down the designers of Defender, Eugene Jarvis and Larry Demar, and flew to Chicago on the last of my savings to crash on Eugene’s couch and spend a few days getting their feedback on the details.

I then spent a frustrating couple of months trying to sell my manuscript, but in hindsight it was too late for a Defender book. I collected some hilarious rejection letters, such as the one from an acquisition editor at Alfred A. Knopf who had apparently never seen a dot-matrix printout before and assumed the entire text was computer-generated. He lectured me on the need for strong narrative in fiction, closing with “I wonder how fictive is the mind of, say, Steve Jobs?”

My lucky break came when Eugene was interviewed by JoyStik Magazine in Chicago, and he told them they should talk to me. I wound up taking a job as a technical editor at JoyStik and moved to Chicago on a few days notice. Playing and writing about video games became my day job, and I could expense rolls of quarters – a dream job for a 24 year-old teenager!

After I was working at JoyStik, I edited the chapter on Free Space into a “Winning Edge” column for the magazine, and that’s the only part of the manuscript that’s ever been published, until today.

Today, some of the remaining Defender enthusiasts are really good at the game, and well beyond the level of player that my book was geared toward. But back when Defender was new, we were all still figuring out its possibilities. We were playing coin-operated games that belonged to others, so we couldn’t open them up and change the settings. So somebody had to be the first to play for an hour, or a day, at factory settings, and 1981 was a great year for Defender players because all of those records were falling and there were contests going on all over the place.

There was a gunslinger mentality, with players coming in to one another’s hangouts to put up attention-getting scores during off hours, or during prime time if you felt ready for a public duel. And unlike today’s global video gaming culture, playing styles and influences were constrained by the need to physically transport yourself to a particular piece of hardware to compete with others. This resulted in playing-style trends like those mentioned in Chapter 11:

In Seattle, where I play, the top players are very aware of the idea of style in Defender playing. Some players even refer to particular styles of play by the part of town where they originated. East Side players (from Bellevue and Kirkland) have the most compassion for the men on the planet’s surface; they never shoot them intentionally, and catch almost every man that goes up. South End players (from Renton, Kent, and Des Moines) like to shoot baiters – they’ll often wait for a few at the end of a wave. North End players (from Wallingford, Lake City, and the University District) are careful and consistent and they play to win.

My book is in some ways just a record of how a particular group of South End players was approaching the game in those days. If you’re into that sort of thing, enjoy.