Power of Two

I’ve spent much of the last two days going through old photos, music and other materials, preparing for my brother Brad’s memorial service this Friday. He died much too young, and quite unexpectedly, but the exercise of reviewing the artifacts of his life is providing me occasional opportunities to remember the fun times.

One such memory was sparked by coming across the manuscript of a column we co-authored in 1996. We were planning a series of columns named “Power of Two,” for the web site of a friend of Brad. As longtime fans of brothers Tom and Ray Magliozzi and their popular “Car Talk” radio show, we were hoping to find a way to apply the same playful brothers-being-brothers routine to technology topics. Brad was living in Seattle, I was living in Chicago, and we wrote the first column in a long series of emails back and forth, taking turns adding a response or rebuttal until we felt it had run its course.

As it turned out, we just did the first column and then we got busy and never got back to it, and the web site where it was published hasn’t had the column online for many years now. But since I found the original manuscript, I decided to post it here for safekeeping.

Power of Two (1996)

Power of Two is two brothers who work with personal computers and write about the consequences. Brad Mahugh is a network technician in Seattle who supports LANs, WANs, and e-mail systems spanning five continents. Doug Mahugh is a custom software developer in Chicago whose clients include progressive small businesses as well as Fortune 500 firms. Between them, they have worked with every major advance in computing technology since 1978, when Doug (the oldest) started writing Fortran programs on punchcards for The Boeing Company. Neither admits to being an acronym addict.

This issue, our geekly bros turn their attention to “Being Digital,” a book by Nicholas Negroponte. It was published in 1995 by Knopf, ISBN 0-679043919-6, 236 pages.

DOUG: Nicholas Negroponte is an electronic media professor at MIT who writes a popular column for Wired magazine. His book “Being Digital” was the most talked-about layman’s book on computer technology of last year, and for good reason. It’s an engaging and entertaining discussion of the fundamental issues of the of the evolving information age. If you’re curious why cable companies are suddenly branching out into other forms of media, or why the Internet is gaining popularity so quickly, read this book.

BRAD: Okay, so I asked for this one for X-mas and read the book mainly because Doug was talking about it and it sounded cool. Sure enough, this is a book whose seemingly random design covers all of the really critical points without using the same old artificial hierarchical approach to assembling text that you might expect from a seasoned academic. “Being Digital” is much more than a mere textbook on the future of information technologies, and Negroponte in his own brilliantly inspired editorial judgment (“Being dyslexic, I don’t like to read”) forsakes the traditional approach with impressive results. Instead of compartmentalizing potential avenues of technical innovation, he treats the reader to brief sections of a few pages that pull you into the discussion and challenge you to imagine what “digital” life might be like. These sections have eye-catching titles like “The Interface Strikes Back” and “Build a Frog, Don’t Dissect One,” making Being Digital a great book to pick up and put down, reead in parts, or just skim through. Negroponte’s goal that “(the reader) should read himself into this book” is well served by the casualness of its design.

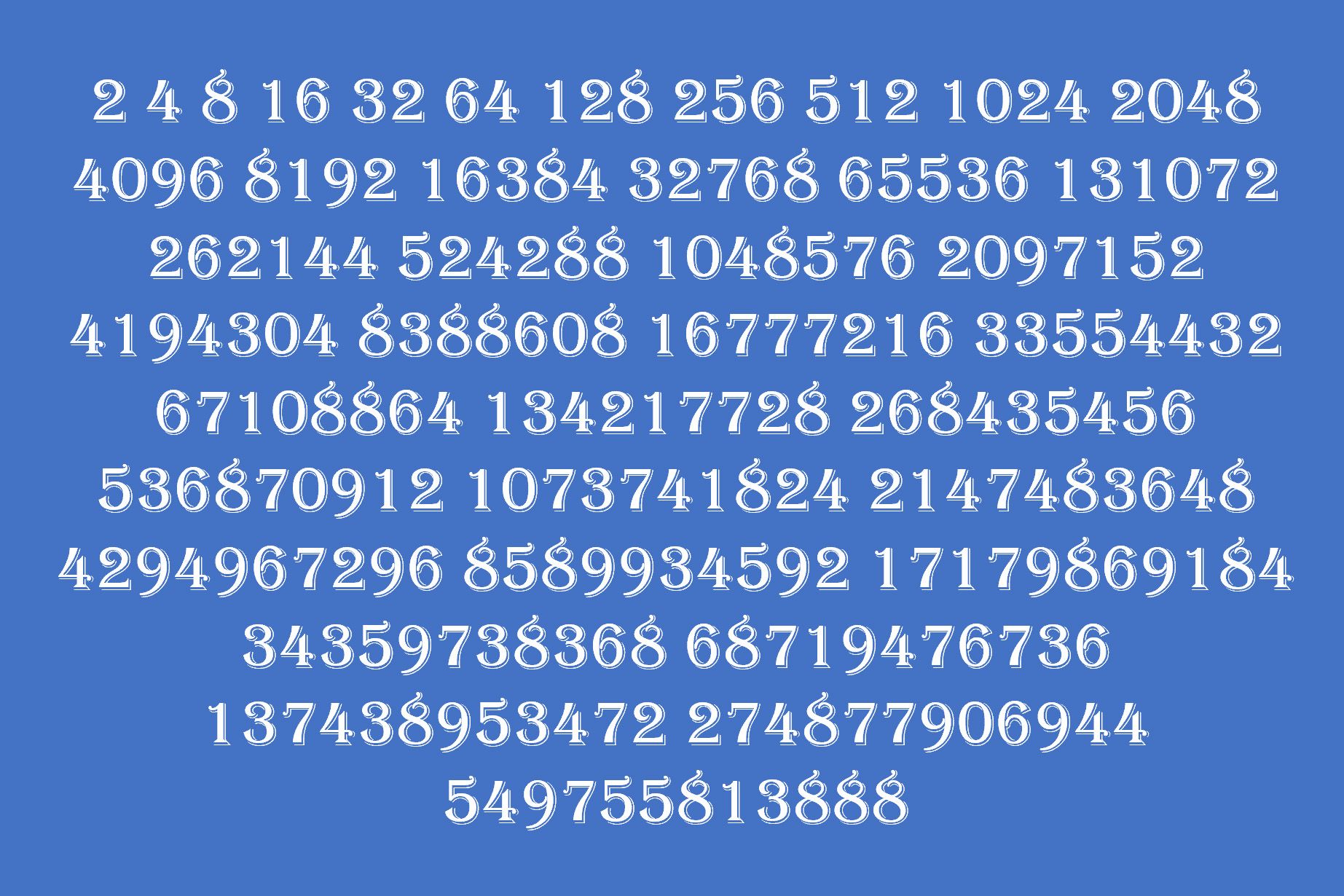

DOUG: Casual or not, Negroponte explains the “1’s and 0’s” perspective with unusual clarity. This is the perspective of hardware designers and machine-language programmers, to whom all computing activity is simply the organized orchestration of 1’s and 0’s. Regardless of which operating system or application you’re running, this is what is really happening inside your PC all day long, and Negroponte makes it interesting and even fun. His explanation of the binary number system, for example, is a model of clear communication:

“Try counting, but skip the numbers that have anything other than a 1 and 0 in them. You end up with the following: 1, 10, 11, 100, 101, 110, 111, etc. Those are the respective binary representations for the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, etc.”

Contrast this with any other written explanation of the binary numbering system, and you’ll see one of Negroponte’s greatest strengths: the ability to write clearly and directly about complex topics. Explaining the binary number system without ever using the phrase “power of two” is clever indeed, and it delivers an important concept to people who wouldn’t have the patience for a more traditional explanation.

BRAD: Patience? Well, yes, it stands to reason that the same people who pay my brother’s hourly rate wouldn’t have the patience to have him teach them how to count to two! But honestly, even though it’s the fundamental underpinnings of everything we do on PC’s, binary arithmetic is not something I’ve found to be a big issue “in the real world”. It’s not a level of abstraction that shows through very often. I always tell aspiring computer geeks “don’t lie awake at night memorizing powers of two like my big brother did — learn how to write Excel macros or edit HTML instead, and you’ll never go hungry!” (Not that Doug actually goes hungry very often.)

DOUG: In spite of his inflammatory rhetoric, Brad knows that the real value of “Being Digital” lies not in the low-level details it exposes, but in the higher-level issues and questions it raises. The author explains how all the existing commerce is one of two types: moving atoms or moving bits. He then shows how the bit-moving business businesses, from banking to publishing, are growing exponentially, while the atom-moving businesses are either relatively flat or — in many cases — disappearing in the face of digital alternatives. His conclusion, for players in the information-based industries, is that “owning the bits or rights to the bits, or adding significant value to the bits, must be part of the equation.”

BRAD: Looking at this from the network side of this bits business, I will say in my realm of experience “bandwidth” has become a cliched term in data communications, like the use of “deficit” or “balanced budget” in a political debate. Somehow, Negroponte is able to put some real clarity and perspective into all the bandwidth discussion that all of us can appreciate, understand and reflect upon – not just those of us in the bit plumbing business.

I enjoyed his attempt to clarify one of the most common misconceptions about telecommunications and existing phone wiring in the home: the notion that the wiring itself is a limiting factor. If people in the United States realized that the same supposedly outdated copper wire that currently handles low-bandwidth voice-only communication could easily be improved and expanded with a few switch replacements in their telco’s central office and this improvement would offer up to 600 times the current rate of throughput as well as the potential for voice and data transfer simultaneously, well it just might spark the consumer demand needed to effect some real change in the status quo (or at least a few more annoying calls for Ma Bell’s customer service people to answer).

DOUG: You mean besides the ones from you? You go postal on them again?

Brad: Ahem! So as I was about to say, Negroponte’s take on the fiber vs. copper debate (which isn’t really a debate so much as a “how soon and how much” topic of discussion) is refreshing and well considered. He’s very clear about how the course of nature and common sense will be fuel the wheels of change:

“Today, fiber is cheaper than copper, including the cost of the electronics at each end. If you come across a condition where this is not true, wait a few months, as the prices of fiber connectors, switches, and transducers are plummeting … One way to look at the transition from copper to fiber is to observe that American telephone companies replace roughly 5 percent of their plant each years, and they replace copper with fiber for maintenance and other reasons. While these upgrades are not evenly distributed, it is interesting to note that, at this rate, in just about twenty years the whole country could be fiber.”

This is solid thinking tempered with accurate information, but he only uses this whole discussion of cabling to set up a bigger and better point: available bandwidth will cease to be the key issue that it is today — the content and control of consumable bits will be a measure of their value, not how fast they can be piped into our homes.

DOUG: On the minus side, Negroponte is less objective in his view of the PC industry, and his background as an ivory-tower researcher sometimes colors his view of the options. He is a big fan of the Macintosh, and he attacks other companies with the same zeal with which he praises Apple. For example, he slams IBM for using the PC moniker in 1981 “in spite of Apple’s having been on the market more than four years earlier.” IBM didn’t invent the PC concept, but neither did Apple, and it’s a disservice to the people of Xerox PARC (Palo Alto Research Center), IMSAI, and Altair to ignore their innovations in the early 1970’s.

Negroponte makes a similar statement regarding Microsoft Windows. Yes, those of us working with PC’s in 1983 were surprised when Microsoft decided to name its upcoming operating system Windows, since that was already a generic term in the PC industry at the time. In fact, after IBM’s “PC” and Microsoft’s “Windows”, people joked that Epson’s next printer would be called “Printer” and Lotus’s next spreadsheet would be called “Spreadsheet”. But Negroponte’s comment about “Apple’s having had (better) windows more than five years earlier” is misleading: the windows concept was pioneered at Xerox PARC many years before Apple started using it. And when Negroponte suggests that imperfect graphics displays are “absolutely unnecessary if hardware and software manufacturers would just use more pixels and throw a little computing power at the problem,” you can’t help wondering whether he has ever paid for a PC with his own money.

BRAD: Nick pay for a PC? You gotta be kidding, bro! The only hardware I could see Nick buying with his own dough would be something that says “Apple” on it.

DOUG: Er, I used the term in its original pre-Jobs, pre-Wozniak connotation: “PC,” a personal computer of any kind. Sorry for the ambiguity that causes in you Gen-X.5ers — I got out of high school before the Apple sales force pulled up in their BMW’s and explained how you can generate a sum of 666 from a clever mathematical manipulation of the letters “P” and “C.” Frankly, I wasn’t warned until it was too late.

BRAD: Well, since I have effectively twice the experience you do with a Macintosh (I have turned one on and off twice!), I will just say that Nick seems to be missing the boat on why Apple is Apple. For this, I need to take you all the way back to the Civil War here (bear with me all you Tom Waits fans!): sure, General Robert E. Lee was top notch, first in his class at West Point, etc. etc. And everybody knows Grant was a drunk who preferred doing battle with a deck of cards and a bottle of corn whiskey in hand. But look who won? My point to this historical non-sequitur: singularly defined excellence is not enough! In this industry, you must be pliable and flexible enough to be able to win in less obvious and proud ways too (ask Mitch Kapor, the developer of Lotus 1-2-3).

DOUG: Hey, don’t pick on Mitch, he’s one of my heros! Long live electronic freedom!

BRAD: Since the whole reason for the success of the PC was its open and cloneable design (which was sort of a Grant-like accident of fate, the exception to the standard Big Blue rule of proprietary development), you’d think Nick would be able to see how Apple’s adaptation of the role of General Robert E. Lee in modern times may have made them a noble and tragic figure for those who care, but in truth only because they chose to preserve the fight for a lost cause (closed systems design) for too long.

DOUG: To paraphrase that famous French philosopher guy, “any man who doesn’t love the Mac at age 20 has no heart, and any man who still loves the Mac at 40 has no brain.”

BRAD: Ou contrare, mon frere! The Mac hasn’t actually been around long enough to apply both tests to the same person — by the 20th anniversary of that 1984 Super Bowl spot, we’ll be able to tell which folks have *neither*. I have my hunches, of course.

DOUG: Me, too. But these are minor complaints, little quirks in a book full of great ideas like “if you have to test something carefully to see the difference it makes, then it is not making enough of a difference.” I love this comment, because as you know, I’m still using PKARC 3.5 (the 1987 version) for all routine file compression chores.

BRAD: Give me a break, you can’t use PKARC to de-compress ZIP files, and everybody’s using ZIP files these days, so I *know* you gotta have a copy of PKZIP handy.

DOUG: Yeah, I’ve got it, but that doesn’t mean I like it. Or use it, unless I have to — sometimes I keep it in an ARC file, PKZIP.ARC, so that I can get at it when I need it, just extract a copy then nuke it. Hell, I should write a batch file to do all that in one fell swoop, just to be silly.

Anyway, when everybody was excited about that bug in PKZIP a couple years ago, I kept smiling and being so “retro” and using my pathetically outdated PKARC, which has never let me down. In this type of software, the improvement over the last few years is *marginal*, people: typically less than 30% reduction in compressed file size, and you have to wait longer to compress and de-compress them. I don’t know about you, but I wouldn’t *walk across the street* for a measly 30% improvement in *anything*. Besides compatibility problems and slower performance, what’s the difference?

“Being Digital” makes a difference, though, by making a important technical issues easily understandable for everyone. It’s full of great stories and insightful observations. The author seems to have learned the history of the PC industry from Apple’s press releases, but his view of the future is bold and compelling. A good read.

BRAD: Damn, I got to agree with my big brother on that one … thumbs up and all the rest. I will, however, argue his introductory claim that this is “the is the most talked-about layman’s book on computer technology of last year” — we all know that Bill Gates’s “The Road Ahead” would unfortunately have to win that title hands down, but “Being Digital” SHOULD be the most talked-about layman’s book on computer technology of the past year.

DOUG: I only know what my clients tell me. I heard two of them rave about Nick’s book last year, which is twice as many as I heard rave about any other book on technology. That makes it “the most talked about technology book on the West side of Chicago,” if nothing else.

BRAD: I’d love to carry on about the average reading level of your clients, but that’s a topic for another day. We’re outta time.

DOUG: And space. Join us next time, when we compare plumbers to poets, and conclude that the world needs both.