My knee in 2025

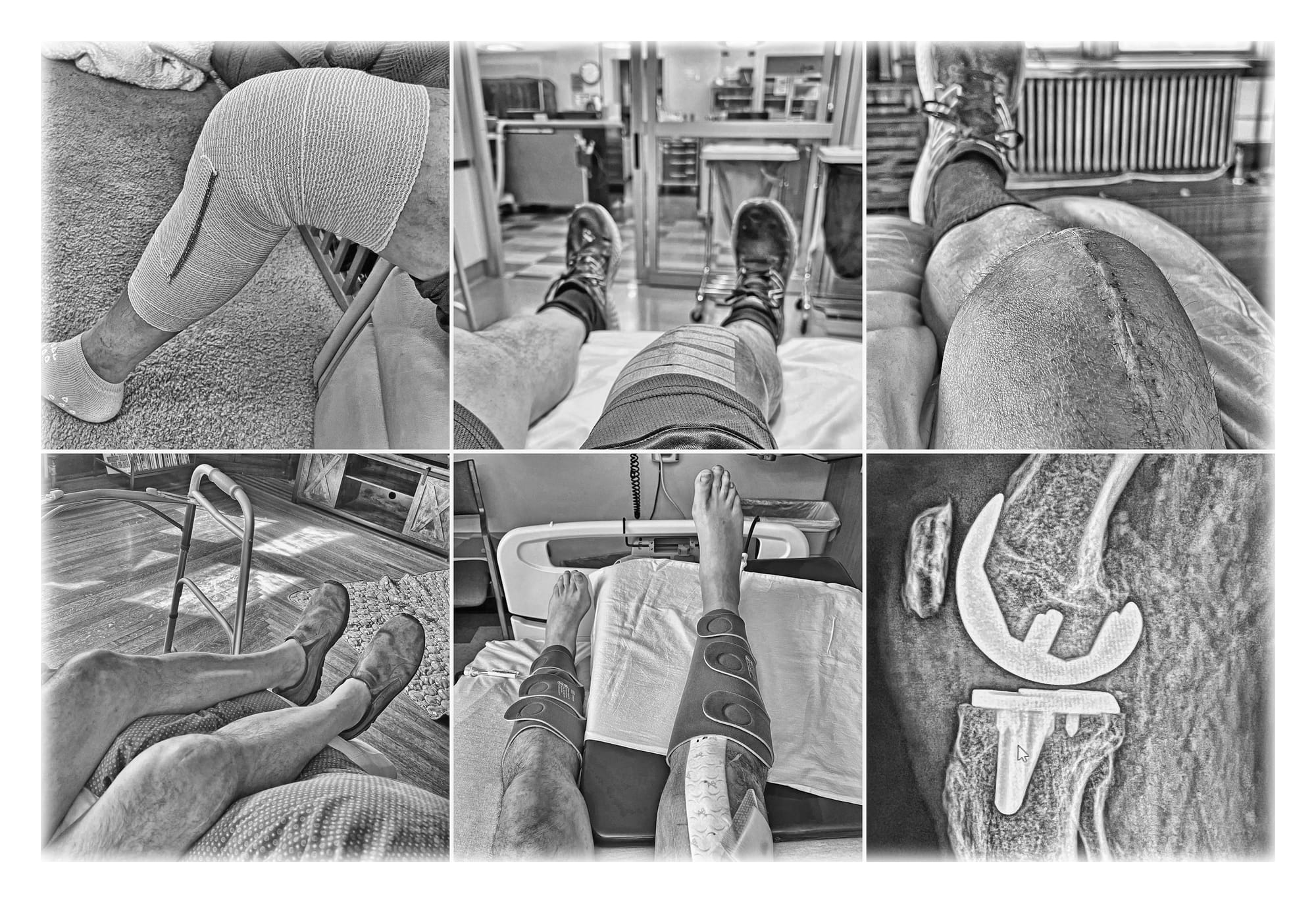

Last week I started putting together a "the year in photos" blog post as I usually do in late December, and as I looked back over my photos it was clear that my replaced right knee had dominated the year. I took fewer photos in 2025 than I usually do in a year, and many of the photos I did take were knee-related.

So I've decided to do two posts: 2025 photos and videos is the usual year-end recap of some favorite photos and videos, and this post is about my knee in 2025: expected and unexpected developments, things I've learned, and a few details I haven't shared before.

I've had two quite different experiences with my knee in 2025. First I had a routine knee replacement in May, with a drama-free and successful recovery. This is a common experience – over a million Americans had a knee replaced this year, and most recoveries go well. So I won't describe many details of that experience below, because most people know someone who've been through it or have gone through it themselves.

I had a more unusual experience in the last few months of the year, when my knee become infected and required an additional surgery and aggressive antibiotic treatments. This occurs in less than 1% of knee replacement patients, so I've shared some details of that experience below, because most of us – thankfully – will never have to deal with it.

Table of Contents

Mornings on Park Street

I knew at the beginning of the year that I'd be getting total knee replacement (TKR) surgery in May, so I started preparing for it in February with physical therapy sessions. One of the biggest factors for TKR recovery is the strength of your quadriceps, and I wanted to spend three months working on that and related conditioning before surgery.

After looking into a few options and talking to a few people, I decided to go with Kevin Stenson, a PT who has been working in Butte for 25 years. His clinic, opened in 2009, is on the east side of Uptown Butte near the massive Belmont Mine headframe, with views of the Highland Mountains from the stationary bikes and weight machines.

Kevin has been a great fit for me, and I've learned a lot from him about knee recovery and also about conditioning and working out in general. He has a relaxed style while still pushing me hard to do what's needed, and he's good at subtly reigning me in when I try to do too much too soon, a recurring situation. Almost all of my appointments with him have been at 7:30AM, and those workouts are a great way to start my day.

When I started working out with Kevin in February, I was expecting to see him for a few weeks then and a few weeks after my surgery. But I liked what I was getting out of post-surgery PT so I extended it, and then I had an unexpected infection cleanout surgery in the fall, which required more PT, and then that recovery got a bit complicated (as covered below) and needed to be extended.

As it turns out, I've spent most of the year doing twice-weekly morning workouts on East Park Street. I watched the Highlands turn white on early mornings in February and March, then watched the snow recede until it was gone by late summer, and then watched the snow come back in the fall. I worked out in darkness in winter and spring, then my 7:30 appointments were well after sunrise through the summer, and now I'm working out in darkness again as the year comes to a close.

TKR recovery

In late 2024 when I posted about my decision to get a knee replaced, I got some advice from a childhood friend and classmate I hadn't heard from in decades. Martin, whom I remember as a big strong teenager, commented that he he'd had both knees replaced in the previous year (by a colleague of the surgeon I was working with, coincidentally), and his recoveries had gone very well. His advice to me was simple: "Remember, PT is your new religion.”

I took that advice to heart, starting three months before the surgery as mentioned above, and I continued to treat PT as my new religion through the rest of year.

When I met with the surgeon Dr. Bruckner two weeks before surgery, I asked him – because he had replaced both of my hips so successfully in 2015 – what he felt the biggest difference was between recovering from hip replacement and recovering from knee replacement. His answer reinforced Martin's advice about making PT my new religion: "with the hips, I probably told you that if you were having pain you should take pain meds and rest, but with a knee, if you're in pain you should take some pain meds and keep working, stay focused on building strength and flexibility."

The TKR surgery in May went well, and I started doing simple exercises on the first day, then re-started working out with Kevin two weeks later back in Butte. That focus on PT often meant prioritizing strength building over pain reduction, as my surgeon had recommended, but it was totally worth it. At the six week follow-up with Dr. Bruckner, he cleared me to work out as hard as I'd like, with no restrictions.

I extended my PT appointments into late August, over three months after surgery, well beyond what had been prescribed or what insurance covered. On my final session with Kevin, we discussed a plan for moving from mostly knee-specific exercises to full-body workouts going forward. I started lifting weights and doing more ambitious exercises such as kettlebell swings. I also started taking longer hikes, at higher elevations, and carrying more weight.

I hadn't worked out that hard in years, and it felt great.

By the final days of September, I was feeling strong and making plans to end the hiking season with a hike to Table Mountain, the highest point in our county. My recovery had exceeded my expectations, and I was eager to enjoy the benefits of all those months of hard work.

A change in plans

My plans for the rest of the year suddenly changed on the evening of October 1st, when I had emergency surgery to clean out a serious staph infection in my new knee. Hiking to the top of Table Mountain was suddenly off the table for 2025; now that's a goal for 2026 instead.

During my week in the hospital after surgery, I wrote up a blog post to let friends know what had happened. At the time, I was just grateful to have my leg and my life, and I didn't get into many details. But there are some things I learned that I've found interesting, so I'll go over some of those below.

How did this happen?

Many people have asked what caused my infection. Where did it come from? How could this happen?

But I've learned from the experts that a more insightful question might be "why doesn't this happen more often?" About 30% of people (including me, apparently) have staphylococcus aureus bacteria living on their bodies, and the vast majority of those people never get a staph infection. If they get a little cut or scratch, some staph bacteria may get in their blood, but their immune system usually kills it quickly and they never know that anything happened.

But things can go awry, in a variety of ways. In my case, I have a new knee made of shiny titanium and tough shock-absorbing polyethylene – an inanimate object with no immune system. So what most likely happened was that I had a cut or scratch somewhere on my skin that allowed some staph bacteria to get into my bloodstream, and a few staph cells made it to the nooks and crannies of my artificial knee, where they could grow and reproduce in peace, with no immune system trying to kill them. By the time I noticed symptoms starting to develop, the infection was too big for my immune system to deal with on its own, so surgical intervention was required to deal with it.

After it was clear I was going to need surgery, I met the man who would perform that surgery: Dr. Stenger, an orthopedic surgeon at St. James Medical Center. Dr. Stenger has done over 300 infection cleanout surgeries, and he has a straightforward no-nonsense style that I found easy to work with.

Dr. Stenger noted that some people want to know all the details and some people don't, and I told him that I always want to know all the details. So he proceeded to explain to me the various surgical options and range of possible outcomes. I'll go over those next.

Deciding on DAIR

There are two types of surgery that orthopedic surgeons most commonly use to clean out an infection in a prosthetic knee joint: two-stage revision arthroplasty, and the DAIR approach (an acronym for debridement, antibiotics, and implant retention).

Option #1: two-stage revision

The National Institutes of Health characterizes two-stage revision arthroplasty with an antibiotic spacer as "the gold standard of treatment." They say that because it has a 90% success rate for permanently eliminating the infection, but it's also a multi-surgery procedure with a long recovery time, and there's risk of a less than perfect recovery.

In the first stage of a two-stage revision, they surgically remove your entire artificial knee – both implants in the tibia and femur, as well as the polyethylene spacer in between. Then they clean things up to remove as much bacteria as possible, including any damaged tissue or bone. After that, they insert a temporary spacer between your tibia and femur that's impregnated with antibiotics, and close your knee back up. For the next three months, it's all about antibiotics treatment to rid your body of the bacteria that caused the infection.

The second stage of a two-stage revision is another surgery, to open your knee back up and install a new knee joint. After that's done, you can finally start working on recovery. But after two surgeries and months of inactivity, the recovery process may take a full year or more, and some patients never fully recover.

Option #2: DAIR

Instead of two-stage revision, we went with the DAIR approach, which I'll describe next.

DAIR offers the possibility of a much quicker recovery, but there's significant risk involved. For about 1 out of 3 patients, the DAIR surgery doesn't succeed in permanently getting rid of the infection, and additional surgery (or surgeries) may be needed.

The NIH has published a literature review that identifies the patient factors that affect the success of a DAIR procedure, and I'm lucky to be in the low-risk group for many significant factors:

- Duration of infection – NIH says DAIR works best within two weeks of the onset of an infection, and I was in surgery within 72 hours of the first symptoms.

- Infecting micro-organisms – NIH notes that DAIR is less successful with MRSA and more successful with MSSA, and my infection was MSSA. (If you're not familiar with those acronyms, there's a section on the difference between MRSA and MSSA below.)

- Surgery type – DAIR is less successful with arthroscopic surgery, and mine was open surgery.

- Antibiotic choice and duration of antibiotic use – there's a bunch of information on that below, but the gist of it is that my antibiotic treatment is among the most successful alternatives.

- Patient's innate immunity – immunocompromised patients have less success with DAIR, but my immune system is strong and healthy.

Based on those factors as well as some other considerations, Dr. Stenger recommended that we use the DAIR approach, and I agreed with this decision after getting a thorough explanation of the issues and options.

The big benefits of the DAIR approach are that there's only one surgery, and they leave your well-anchored implants in place, both of which will theoretically lead to faster recovery. Not as quick as TKR in most cases, but much quicker than recovery from two-stage revision.

After discussing the options, Dr. Stenger recommended – and I agreed – that DAIR was the way to go. Based on the various factors that affect the success of DAIR treatments, I'm likely to be among those for whom it offers the best path forward.

Dr. Stenger also told me about the worst-case scenario. Twice in his career he has had to amputate a patient's leg to prevent them from dying of sepsis, because the infection kept coming back no matter what they did. He reassured me by noting that those patients were both former drug addicts with compromised immune systems, so that outcome was unlikely for me.

Infection cleanout surgery

After deciding on the type of surgery on the morning of October 1, we scheduled my surgery for later that day. The sooner the better, but Dr. Stenger had two critical surgeries already on his schedule that day, so my surgery was planned for 5PM.

While waiting for my surgery, I had a task to handle. The DAIR process entails removing the polyethylene spacer between the knee joint implants and replacing it with a new sterile spacer of the exact same dimensions, ideally from the same manufacturer as the original. So in the hours before my surgery, I made phone calls to the office of the surgeon in Bellevue who had replaced my knee, to track down those details for Dr. Stenger. After we had the size and model numbers of the components of my artificial knee, Dr. Stenger contacted the local manufacturer's rep to secure an identical polyethylene spacer, and then we were ready for surgery.

The anesthesiologist told me the next day that I had been getting incoherent in the hour before my 5PM surgery, despite having not had any anesthesia yet. This was concerning to them, because a lack of mental clarity while your body is fighting an infection can be a sign of sepsis.

Last photo before surgery on the left, first photo after surgery on the right.

I was out cold for the surgery, of course, but I've had both the surgeon and the nurse practitioner who assisted in the surgery tell me what went on during those two hours. They started by opening up my right knee along the same line that was used for the TKR surgery, and then removed infected scar tissue and started cleaning any obvious signs of infection.

They also removed the polyethylene spacer and thoroughly disinfected the exposed surfaces of the implants, and checked the implants to make sure they were well-anchored and no bacteria had been able to get underneath them. The surgeon carefully tapped both of my implants with a hammer, and they didn't vibrate at all. That solid anchoring is a testament to the skill of the surgeon who replaced my knee.

Finally they installed the new polyethylene spacer and closed things back up, with a row of metal staples to hold the wound closed. I spent that night in the ICU because of the sepsis concerns, but by early the next morning my white blood cell count was back to normal, indicating my body was no longer fighting a big infection.

Later that day I was moved to a hospital bed up on the 5th floor, and that's when I transitioned from the D (debridement surgery) phase of DAIR to the A (antibiotics treatment) phase.

Meeting Dr. Pullman

Moving from the D phase to the A phase meant moving from being in the care of an orthopedic surgeon to being in the care of an infectious diseases doctor. The day after surgery, I met Dr. Pullman, the infectious diseases specialist handling my antibiotics treatment. He is board-certified in infectious diseases, internal medicine, and critical care, all of which are great fits for what I was going through. Dr. Pullman has been practicing medicine in Butte for decades, and we're lucky to have him.

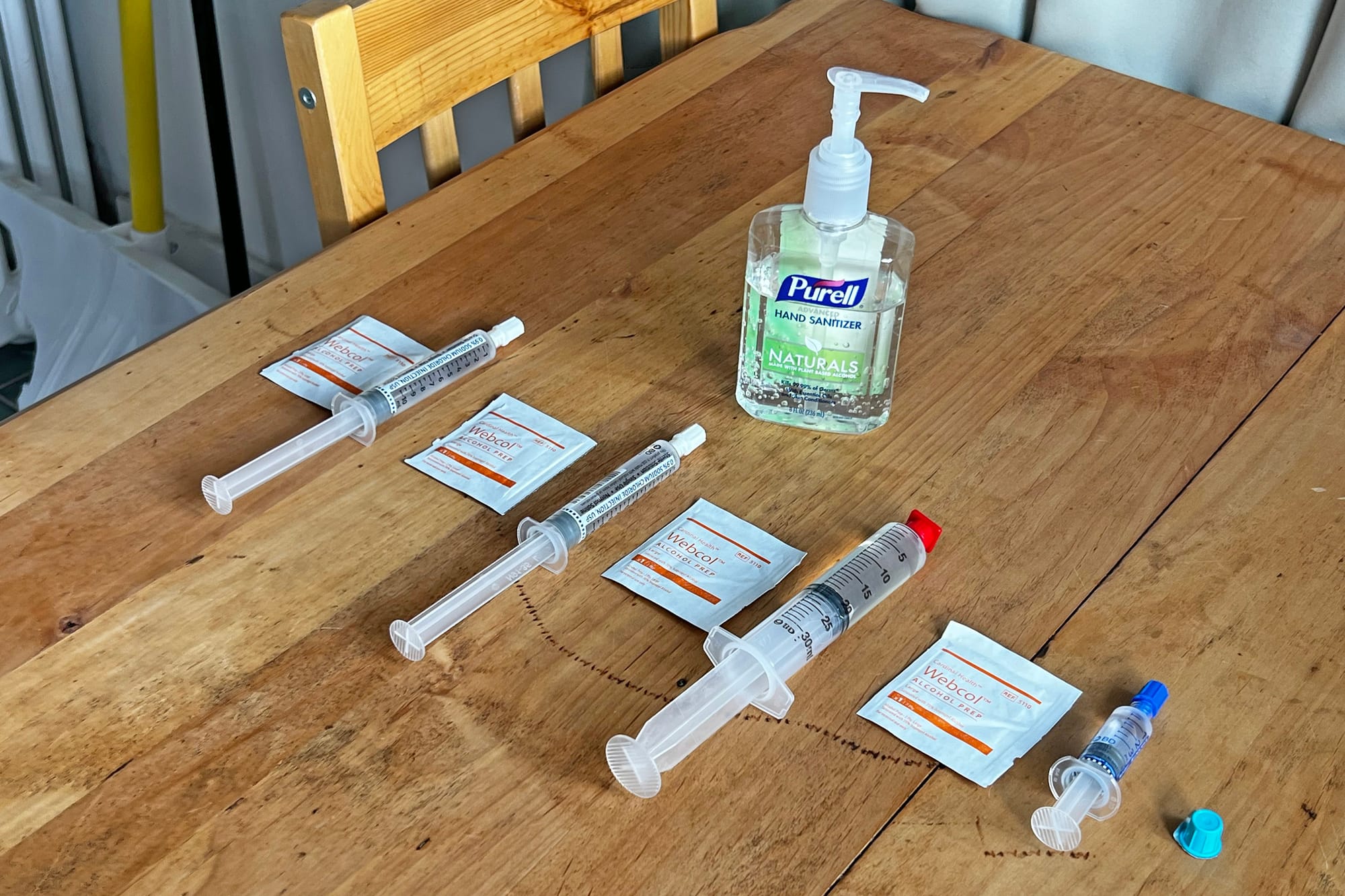

As Dr. Pullman explained to me, the first order of business would be to do whatever it takes to kill any remaining staph cells in my body. He put me on IV antibiotics while I was in the hospital for a week after surgery, and then I went home with a PICC line installed in my right arm, and for the next 6 weeks I injected myself with antibiotics every 8 hours at 6AM, 2PM, and 10PM. I saw Dr. Pullman and his PA Erin several times during that phase, and every week their team drew blood for labs to monitor how things were going.

The antibiotic routine I did three times a day for six weeks after surgery.

Struggling with recovery

After I got home from the hospital, I felt like I knew exactly what to do because I'd been through a successful recovery from TKR surgery just a few months ago. I started putting weight on the joint right away, going up and down stairs and doing PT exercises just like I'd been doing in the first weeks after TKR surgery. I had rocked a knee recovery already this year, and felt like I was on my way to rocking another one.

As I learned in my first follow-up with the surgeon, this was not the right approach at all. Building strength and flexibility is job one after TKR surgery, but after an infection cleanout surgery job one is to get the infection totally under control. This means letting your body heal from the trauma of debridement surgery while you're injecting IV antibiotics several times a day.

I had more swelling than I should have at this point, and that appeared to be caused or at least exacerbated by the exercises I was doing. So Dr. Stenger increased my blood thinner meds and told me to focus on bed rest, ice, and elevating my knee above my heart until four weeks after surgery, when I would start PT sessions again with Kevin.

The swelling was a little better when I started PT sessions in late October, but after workouts my knee would often swell up, and then I'd need to back off on exercise for a while. I was on this roller-coaster through November and into early December, repeatedly thinking I was on track to start rebuilding strength and then needing to take a couple of days of bed rest and ice and elevation to deal with increased pain and swelling.

After my TKR surgery, I had felt like I was growing steadily stronger each week, but it felt different this time around. At times I questioned whether I was making progress or not.

PT exercises at home in late November.

I had been expecting a slow recovery from my infection cleanout surgery, but after two months it felt like things were going even more slowly than they should be. I kept having swelling and pain, and ice and elevation didn't always help. It was frustrating to not be able to work as hard on my recovery as I wanted to – every time I pushed harder on PT, my knee would have increased swelling and pain, and we'd have to back off until that subsided.

A story untold

I've always been pretty open and transparent about posting online the details of what's going on in our life. In part that's been driven by the fact we post about the dogs every day, and many people who love our dogs have come to expect those posts and look forward to them. If I suddenly stop taking the dogs out on walks or hikes, I usually explain why.

But in early December, I had a setback that I've not posted about before. I was struggling with my knee recovery and not getting out with the dogs much around that time anyway, so it felt like there wasn't any change that needed explanation. And frankly, I was getting really tired of talking about my knee.

Chills and fever

On the afternoon of Saturday 12/7, Megan and I went out to lunch at Sparky's in Uptown Butte. It was a sunny day with temperatures just above freezing, and on the short walk from my truck into the restaurant I started shivering hard.

That's not like me. I love cold weather, enjoy polar plunges and that sort of thing, and I can't remember the last time I shivered. It took a long time to warm up in the restaurant, and then I shivered again after walking across the parking lot when we left.

So I went home and huddled under an electric blanket for a while to get good and warm. I was still feeling a bit off that evening, and I decided to check my temperature. I had a fever of 102.1F.

Dr. Pullman had given me his personal cell number, and told me to call any time night or day if I had any concerns or questions. In particular, he said to call if I developed a fever. It was great to have that lifeline when this situation arose on a Saturday evening, and I sent him a text summarizing what was going on. He immediately called me back.

He said to go straight to the ER, where they would check my vital signs and draw blood to do labs. He said to have them call him after they had the lab results, before prescribing any new medications.

Megan drove me to the ER. They checked my vital signs, and my fever was a bit lower, which was good to see. They drew blood and sent it to the lab, and they also did x-rays. I told the ER doctor what Dr. Pullman had said, and she was glad to hear that he was up to speed on my situation and available for consultation. I've had similar reactions from other medical professionals when I mention his name – it's nice that he is held in such high regard by his peers and they want and appreciate his advice.

Long story short, that evening in the ER they couldn't figure out what was going on. The fever made it look like I was having a recurrence of an infection, but my white blood cell count was normal. And the fever continued to drop. When it got down to 99.7F, they decided to discharge me with no new treatment. Dr. Pullman would see me Monday morning for a more detailed analysis, and if my fever started rising again I should come back to the ER. But my fever continued to drop, and my temperature was normal all day Sunday.

Dark days in December

Monday morning I visited Dr. Pullman's office for more tests. They drew blood for a C-RP (c-reactive protein) test, and the results showed I had increased inflammation in my body. So it looked like I was fighting some sort of infection in my knee, despite my white blood cell count being normal. Bummer.

They also withdrew some synovial fluid (joint lubricant, essentially) from inside my knee to check for the presence of bacteria. The synovial fluid cultures wouldn't be back until Thursday, but those would identify exactly what type of bacteria was in my knee.

Recurrence of an infection in my knee was frightening and depressing. Would I be headed back in for another surgery? Had I slipped to the other side of the odds and become one of those 30-50% of patients for whom the DAIR procedure doesn't work? Would I now need to have a two-stage revision, meaning two more surgeries in addition to the two I'd already had? This sort of self-talk drove me into a downward spiral. I felt like I had worked hard for months, doing all the right things and recovering strong, and now I was back in a still unresolved situation that could end in a variety of ugly ways.

Those next three days of waiting for the cultures on my synovial fluid felt like forever. I still had the pain and swelling that had been interfering with my PT workouts, and I knew it was probably something bad, but I didn't have any answers yet.

I have a favorite Marcus Aurelius quote for times like these, and I thought of it while waiting for the test results.

“It is my bad luck that this has happened to me.” No, you should rather say: “It is my good luck that, although this has happened to me, I can bear it without pain, neither crushed by the present nor fearful of the future.”

Because such a thing could have happened to any man, but not every man could have borne it without pain. So why see more misfortune in the event than good fortune in your ability to bear it?

– Marcus Aurelius

Test results

Late Thursday afternoon, I got a call from Dr. Pullman's nurse. The results for the cultures on my synovial fluid had come in, and I had staphylococcus aureus in my knee. We now had confirmation that the infection was back (or more likely, had never quite disappeared), and this explained the recurring pain and swelling after working out, and the fever and chills I had experienced.

Now that he knew exactly what was going on, Dr. Pullman put in place an aggressive plan to eradicate this stubborn infection. I stopped taking the antibiotics that I had been on, and the next morning I would be starting a new treatment plan based on dalbavancin and rifampicin.

That night, I drank the most I have all year: three strong Manhattans.

Good timing on the drinks, as it turned out – I learned the next day that I couldn't have any alcohol for the next three months because of the rifampicin. Oh well, I didn't drink for two months after TKR surgery in May, and also for six weeks after DAIR surgery in October. Three more months of teetotalling, here I come.

Protective biofilm

How could some bacteria have survived all of the IV antibiotics I'd taken in the hospital and for six weeks afterward? The most likely answer is that some staph cells survived by building and then hiding under a protective microbial biofilm on the surface of my artificial knee.

The concept of bacteria hiding under a microbial biofilm is something infectious diseases experts deal with often, but I had never head of it. The Wikipedia page on biofilms reads like something out of science fiction.

The basic idea is that Gram-positive bacteria (bacteria with tough external cell membranes, such as the staphylococcus aureus I was dealing with) can group together on an inert surface such as an artificial knee and then cover themselves with a protective layer that helps evade a variety of threats, including antibiotics. These little "cities for microbes" have existed for over three million years according to fossil records, and arose as an evolutionary self-protection mechanism for bacteria and similar organisms, because conditions in those primitive times were too harsh for their survival.

Time for the big guns

The combination of dalbavancin and rifampicin that Dr. Pullman put me on is a powerful treatment for eradicating a variety of infections. I'll share here a bit of what I've learned about this treatment.

Dalbavancin is an antibiotic known for its long-lasting efficacy and tissue penetration. The first dose of dalbavancin typically kills up to 99% of bacteria within 24 hours, and the second dose usually finishes off the rest. Dr. Pullman was one of the doctors involved in early clinical trials of dalbavancin while it was being developed (this one, for example), so he knows exactly how it works and when to use it.

Rifampicin is an antibiotic used to treat tuberculosis, leprosy, and Legionnaires' disease, among other things. When used in combination with dalbavancin, it helps the dalbavancin penetrate even more effectively into soft tissue, bone, and everything else in your body. It's so invasive that it turns all of your bodily fluids orange, and has some potentially uncomfortable (but not dangerous) side effects.

The biggest downside to this treatment is that the dalbavancin is hard on your kidneys and the rifampicin is hard on your liver. I'm lucky to have healthy kidney and liver function, so those weren't issues for me, but we had to do blood work before each dalbavancin infusion to make sure my kidneys were ready for it.

MRSA vs MSSA

Because I'm on dalbavancin, I've been asked a whether I have methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). No, I have methicillin-sensitive staphylococcus aureus (MSSA), as identified by the culture done on synovial fluid withdrawn from my knee earlier this month. Dalbavancin happens to be a common treatment for MRSA infections, but it's effective against both.

It's worth noting that the distinction between MRSA and MSSA is more subtle and complex than you might think, based on their names. Either one can kill you quickly if not treated, but there are proven effective treatments for either one, too. MRSA is resistant to some antibiotics, but there are other antibiotics that handle MRSA very effectively, such as dalbavancin.

The important thing is that your infectious disease doctor knows which one they're dealing with, so that they can prescribe effective treatment.

Heading into 2026

The dalbavancin infusions started reducing my infection pain and swelling almost immediately, and as I write these words – a week or two after the second and final infusion – I have almost no swelling, for the first time since the surgery on October 1st. I have more pain than I did at this point (~12 weeks) after the TKR surgery, but it's healthy "recovering from surgery" pain and not that creepy infection pain that I felt in late September and again in early December.

My knee has been through quite a year. But after the emotional and physical lows of two weeks ago, when I was waiting for the culture results on my synovial fluid and wondering if the nightmare would ever end, it's great to be heading into 2026 feeling in control of my own destiny. There are no guarantees in life, but right now things are looking good.

Kevin the physical therapist and I have started ramping up my exercise routine after the second dalbavancin infusion, and that's going well. I was originally scheduled to be done with PT in mid-December, but the orthopedic surgeon has extended my PT appointments for an additional six weeks into late January, and we'll probably extend them again after that if things are going well.

During the final week of December, I've had the best workouts I've had since September, including all of my current PT exercises as well as a variety of kettlebell routines. And most importantly, I've had no increase in pain or swelling afterward. It feels like I'm finally back on track.

I'll end this long post with a video clip showing exactly where things stand heading into the new year. I'm still not getting full extension, and limping a bit from the pain, but I'm grateful to be able to walk up a gentle hill with Megan and the dogs, and looking forward to much bigger hills in the future.

Thanks to everyone who has encouraged and supported me on this journey!

taking a walk on Christmas Day