Doc Lynde

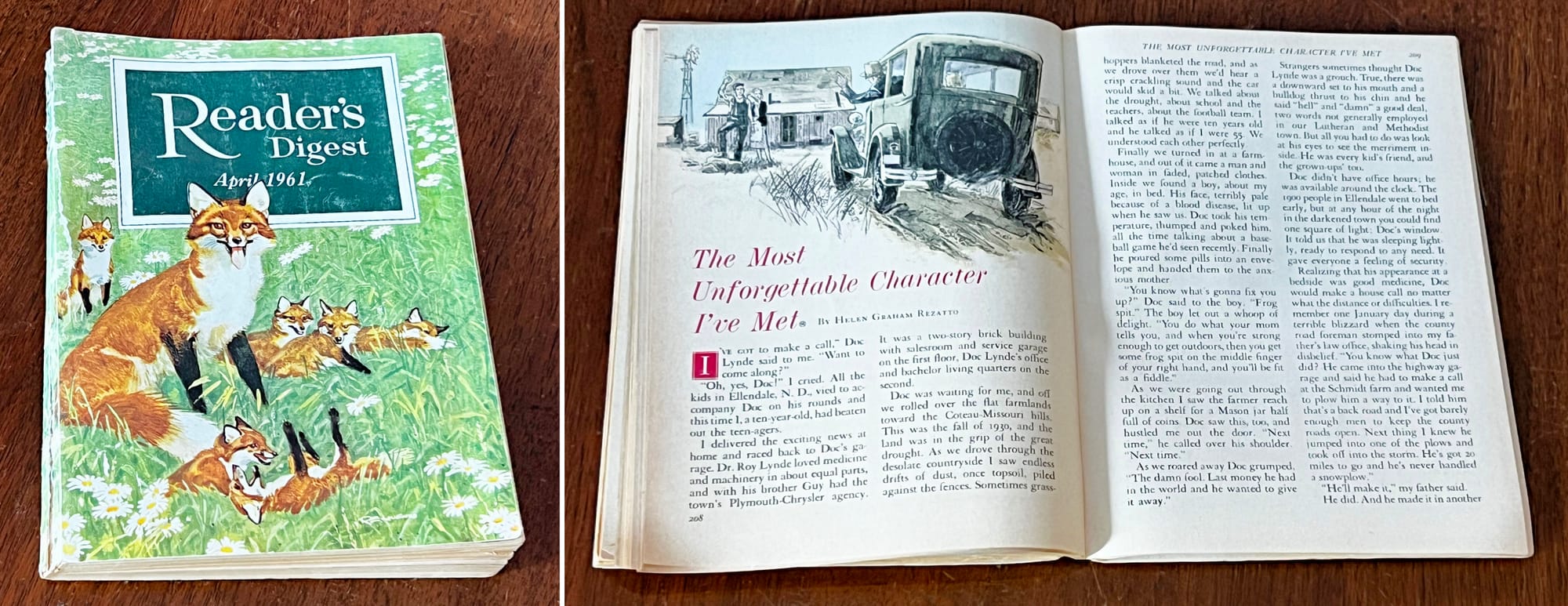

Beginning in 1939, Reader's Digest magazine had a recurring feature entitled "The Most Unforgettable Character I've Ever Met," in which a writer would tell the story of an unforgettable person they'd known who had a big impact on their life. From the 1950s through the early 2000s Reader's Digest was the best-selling consumer magazine in the United States, and The Most Unforgettable Character I've Ever Met was its most popular series.

In April 1961, my great-great-uncle Dr. Roy "Doc" Lynde was featured as The Most Unforgettable Character I've Ever Met, in an article written by Helen Graham Rezatto. I recently tried to find an online copy of this article, but the only transcriptions I've found are low quality (full of typos and omissions), or scanned PDF versions that are hard to read. So I decided to create this blog post, which includes an accurate transcription of the article.

Doc and Guy Lynde were larger than life figures in Dickey County, North Dakota, and I grew up hearing stories of them from my mother and others in the family. Among other things, Doc delivered my mother and uncles and many other family members. Without further ado, here's the story of Doc Lynde as remembered by Helen Graham Rezatto.

The Most Unforgettable Character I've Met

By Helen Graham Rezatto, as published in Reader's Digest, April 1961

"I've got to make a call," Doc Lynde said to me. "Want to come along?"

"Oh, yes, Doc!" I cried. All the kids in Ellendale, N. D., vied to accompany Doc on his rounds, and this time I, a ten-year-old, had beaten out the teen-agers.

I delivered the exciting news at home and raced back to Doc's garage. Dr. Roy Lynde loved medicine and machinery in about equal parts, and with his brother Guy had the town's Chrysler-Plymouth agency. It was a two-story brick building with salesroom and service garage on the first floor, Doc Lynde's office and bachelor living quarters on the second.

Doc was waiting for me, and off we rolled over the flat farmlands toward the Coteau-Missouri hills. This was the fall of 1930, and the land was in the grip of the great drought. As we drove through the desolate countryside I saw endless drifts of dust, once topsoil, piled against the fences. Sometimes grasshoppers blanketed the road, and as we drove over them we'd hear a crisp crackling sound and the car would skid a bit. We talked about the drought, about school and teachers, about the football team. I talked as if he were ten years old and he talked as if I were 55. We understood each other perfectly.

Finally we turned in at a farm house, and out of it came a man and woman in faded, patched clothes. Inside we found a boy about my age, in bed. His face, terribly pale because of a blood disease, lit up when he saw us. Doc took his temperature, thumped and poked him, all the time talking about a baseball game he'd seen recently. Finally he poured some pills into an envelope and handed them to the anxious mother.

"You know what going to fix you up?" Doc said to the boy. "Frog spit." The boy let out a whoop of delight. "You do what your mom tells you, and when you're strong enough to get outdoors, then you get some frog spit on the middle finger of your right hand, and you'll be fit as a fiddle."

As we were going out through the kitchen I saw the farmer reach up on a shelf for a Mason jar half full of coins. Doc saw this too, and hustled me out the door. "Next time," he called over his shoulder. "Next time."

As we roared away Doc grumped, "The damn fool. Last money he had in the world and he wanted to give it away."

Strangers sometimes thought Doc Lynde was a grouch. True, there was a downward set to his mouth and a bulldog thrust to his chin and he said "hell" and "damn" a good deal, two words not generally employed in our Lutheran and Methodist town. But all you had to do was look in his eyes to see the merriment inside. He was every kid's friend, and the grownups' too.

Doc didn't have office hours; he was available around the clock. The 1900 people in Ellendale went to bed early, but at any hour of the night in the darkened town you could find one square of light: Doc's window. It told us that he was sleeping lightly, ready to respond to any need. It gave everyone a feeling of security.

Realizing that his appearance at a bedside was good medicine, Doc would make a house call no matter what the distance or difficulties. I remember one January day during a terrible blizzard when the county road foreman stomped into my father's law office, shaking his head in disbelief. "You know what Doc just did? He came into the highway garage and said he had to make a call at the Schmidt farm and wanted me to plow him a way to it. I told him that's a back road and I've got barely enough men to keep the county roads open. Next thing I knew he jumped into one of the plows and took off into the storm. He's got 20 miles to go and he's never handled a snow plow."

"He'll make it," my father said.

He did. And he made it in another storm, too, a few winters later. That time he borrowed a handcar and we watched him head down the railroad tracks, pumping for all he was worth, to see a sick man in the north part of the county. It was midnight before he got home, by the same method.

Doc's bedside manner was unique. He'd enter the sick room cracking jokes or telling stories, and never give the patient a chance to list his complaints. But all during his monologue he would carefully probe, touch, look, analyze. His theory was that if he ever appeared to take the symptoms seriously, the patient would imagine he was sicker than he really was.

Actually, Doc's diagnostic skill was amazing, and he was ahead of his time in treatment. He massaged polio victims before Sister Kenny was heard of, and he gave thrombosis patients limited exercise when the rest of the country was giving only bed rest. Hypochondriacs and malingers received short shrift, however. "Damn it," he'd say to a patient. "I wish I had your heart."

The Lyndes' garage was an after-school hangout for kids. We delighted in the practical jokes Doc and his cronies played on one another. We laughed when they laughed, and felt grown-up. Doc always treated us as if we had good sense and opinions that deserved an audience.

The town's No. 1 sports fan, Doc didn't miss a single high-school game if he could help it. When the games were out of town, he'd pile his car full of kids and off we'd go to cheer for Ellendale. When we grew older, Doc would loan us brand-new cars out of the showroom for joy rides and out of town games. (He still carries special insurance to cover this.) He never said, "be careful." He said, "take her out and see if she's any good." And because he assumed we were responsible, we were.

I never had an accident with one of Doc's cars, but I did with my father's. I wrinkled a fender against a telephone pole, then drove the car to Doc's garage and broke into tears. "Hell," he said. "You didn't do much damage. We can fix that so your dad will never know."

He and Alvin, his mechanic, went to work on that fender and it came out smooth and shiny, and Dad never did know. No charge, of course.

Ray's Café was another hangout, where we went for sodas after school. Whenever Doc happened to drop in, every booth would set up a clamor for him to sit there. One time he paused before the booth where I was jammed in with seven other girls, looked directly at me (I thought) and said, "Damn funny thing. All the kids I deliver turn out to be the best looking."

I blushed with pleasure and pride, then suddenly realized that every girl in the booth had been delivered by him. Still, we each took it personally.

My first really objective view of Doc came after I had gone away to college and returned home for Thanksgiving vacation. Visiting his office, I observed his habit of dipping the thermometer in alcohol, then wiping it on his necktie before putting it in a patient's mouth, and noticed how he allowed Tom, his big striped cat, to sleep in the baby incubator when it was not in use. So what? Nobody every got sick from the germs on Doc's tie, and no baby objected to Tom's use of the incubator.

I made a few country calls with Doc, but now he had a new system of priorities: any medical student who was home vacationing had first rights. At least ten boys from Ellendale were becoming, or had become, doctors because of Doc's inspiration – and often with the help of his cash. Kenneth Leiby was one of the medical students that fall. One morning as I was talking with Ken's mother, Doc's car came down the street. Ken was with him and his face was split with a triumphant grin. Even Doc was allowing himself a small Cheshire-cat smile. Ken jumped out of the car and came racing toward us.

"Do you know what happened?" he cried. "We were on this OB case about 50 miles out in the country, and she delivered at about six this morning. Well, Doc has the baby up by the heels and is spanking some wind into it when he turns to me and says 'I got mine, now go get yours.' gee, she was having twins – and I delivered a baby! What do you think of that?"

We thought it was pretty wonderful, and no one was prouder than Doc.

After college I married, and in 1943 my husband went off to war, leaving me in New York, pregnant. I went to an immaculate, efficient obstetrician with a starched nurse and gleaming equipment, and I hated every minute of it. I wanted on old, cluttered medical office over a garage. I went home. Doc Lynde had delivered me, and it was he who delivered my baby son. With my husband away, it gave me a comforting sense of the continuity of life.

Doc was always there when needed. one afternoon while my father was working in the garden he had a heart attack. Doc was at our house in minutes and this time there were no jokes. Crisply he ordered me, "Run down to the garage and tell Alvin to bring the oxygen tank, the one we've been using to weld broken springs."

When we returned with the tank we found that Doc and my mother had improvised a tent with bed sheets draped over the fourposter and pinned down to the mattress. He inserted the valve of the oxygen tank under the sheets and began turning it off and on by hand. This makeshift arrangement needed constant attention and Doc was on his knees with it for four hours straight. He saved my father's life. It was this kind of devotion he gave to every sick man and woman and child in the county.

Despite other heart attacks, my father lived an active life for nine more years. Then even Doc Lynde could do no more. After my father's funeral the family returned to the bleakness of an empty house. Each sat with his own heavy burden of loss. Suddenly up the sidewalk came Doc. He entered the house briskly, tossed his hat and coat in a corner and said, "Well now, that was a might fine speech the minister made about Fred. Don't you think so?"

The text had been from Timothy: "I have fought a good fight, I have finished my course, I have kept the faith." Doc grinned at us. "Now, you can't deny it, Fred did have some good fights."

My father had indeed been a strong-willed, rugged individualist. Doc now began to recall his more notable legal and political battles, and we found ourselves smiling, then laughing. Soon we were immersed in wonderful, sustaining memories of the living man. Doc helped us through that first day without our even realizing that we were his patients, that he was prescribing the potent medicine of good memories.

It took our town a long time to discover that Doc was growing old. He was so much a part of our daily lives that we failed to notice the accumulation of wrinkles on his face, or that he paused more and more frequently to catch his breath. It was hard to face the fact that one day the beacon light on the second floor of the garage would be extinguished.

Suddenly we all wanted to express to Doc how we felt about him. But how? Then someone thought of giving him a surprise party on his 76th birthday. On that evening he was taken out for an automobile ride. As the car approached the high school Doc saw the drum majorettes standing by the gym and he exclaimed, "Damn it, have I forgotten a game?"

His host suggested they stop and find out. As Doc stepped from the car the majorettes surrounded him and escorted him in. A mighty roar went up from the residents of Ellendale and Dickey County, and then the thong burst into "Happy Birthday." Doc looked stunned and glanced behind him as if to escape, but the drum majorettes were between him and the door. With a sheepish grin on his weather-beaten face, he took the place of honor at the head table.

There were skits, speeches, and gifts. Dr. Kenneth Leiby, the boy who had delivered the twins with Doc and was now a successful general practitioner in New Hope, Pa., had commissioned a large oil portrait of Doc, painted from photographs, which he now presented to the community.

At one point during the speeches the toastmaster said, "Of course, since Doc is a bachelor he has no kids."

"I'm Doc's kid," squeaked a three-year-old, jumping up.

"I'm Doc's kid," called out a young housewife, standing.

"I'm Doc's kid," boomed the town newspaper editor, rising to his feet.

One by one, people identified themselves until there was a great throng standing. They looked at Doc and he looked back at them and suddenly his chin began to quiver. We had found a way to thank him. Our very existence was our tribute to his skilled and loving hands.

In recent years we've tried to honor Doc in other ways. We built the Dr. Roy Lynde Memorial Nursery section of the county hospital. On the 50th anniversary of the day he began medical practice after graduating from the University of Minnesota, we held a civic holiday with a parade and a double-header during which we dedicated the ball park at the Dr. Roy Lynde Memorial Athletic Field.

Today he is 86. The dust in his office is undisturbed, for his instruments are now relics of the past. When he leaves the garage to go to the restaurant for dinner he walks very slowly and, should he falter, a dozen people are at his side. Each night a different neighbor looks in on him to be certain he's all right. During the week the population of Ellendale parades past his chair in the garage just to say, "Hi, Doc." The might force of the love he has given others over the years now returns to range protectively around him.

I look at him and think of all the sick people he's held in his arms, the bills he's forgotten, the joke's he's laughed at, the kids he's spoiled, the kind deeds he's hidden. And I think of the richness he's brought to our town. Each of us has tried to be a little bit like Doc. None of us made it all the way, but we're more understanding and generous and loving than we would have been if he hadn't lived among us.

Could any man hope to accomplish more?

-###-